I can't seem to shake a preoccupation that continues to surface whenever I try and come to some synthesis of literacy. I am dogged by a persistent dichotomy. On the one hand, literacy is a skill to be mastered, which involves the methodological development of the formal characteristics of language and of the written code. On the other hand, literacy is a creative, communicative practice that calls upon the imagination, the intellect and social cognition, which is much less mechanical and much more about craft, application and growing expertise.

So ... whilst a learner may master the mechanical features of literacy through practice, revision and integration, the applied aspects of literacy require one to negotiate concepts of context, convention, intention, prior knowledge and (possible) meanings, which are not so formally defined.

This integration of form with intention reflects remarks from British philosopher Ray Monk (1999):

"The reason computers have no understanding of the sentences they process is not that they lack sufficient neuronal complexity, but that they are not, and cannot be, participants in the culture to which the sentences belong. A sentence does not acquire meaning through the correlation, one to one, of its words with objects in the world; it acquires meaning through the use that is made of it in the communal life of human beings."

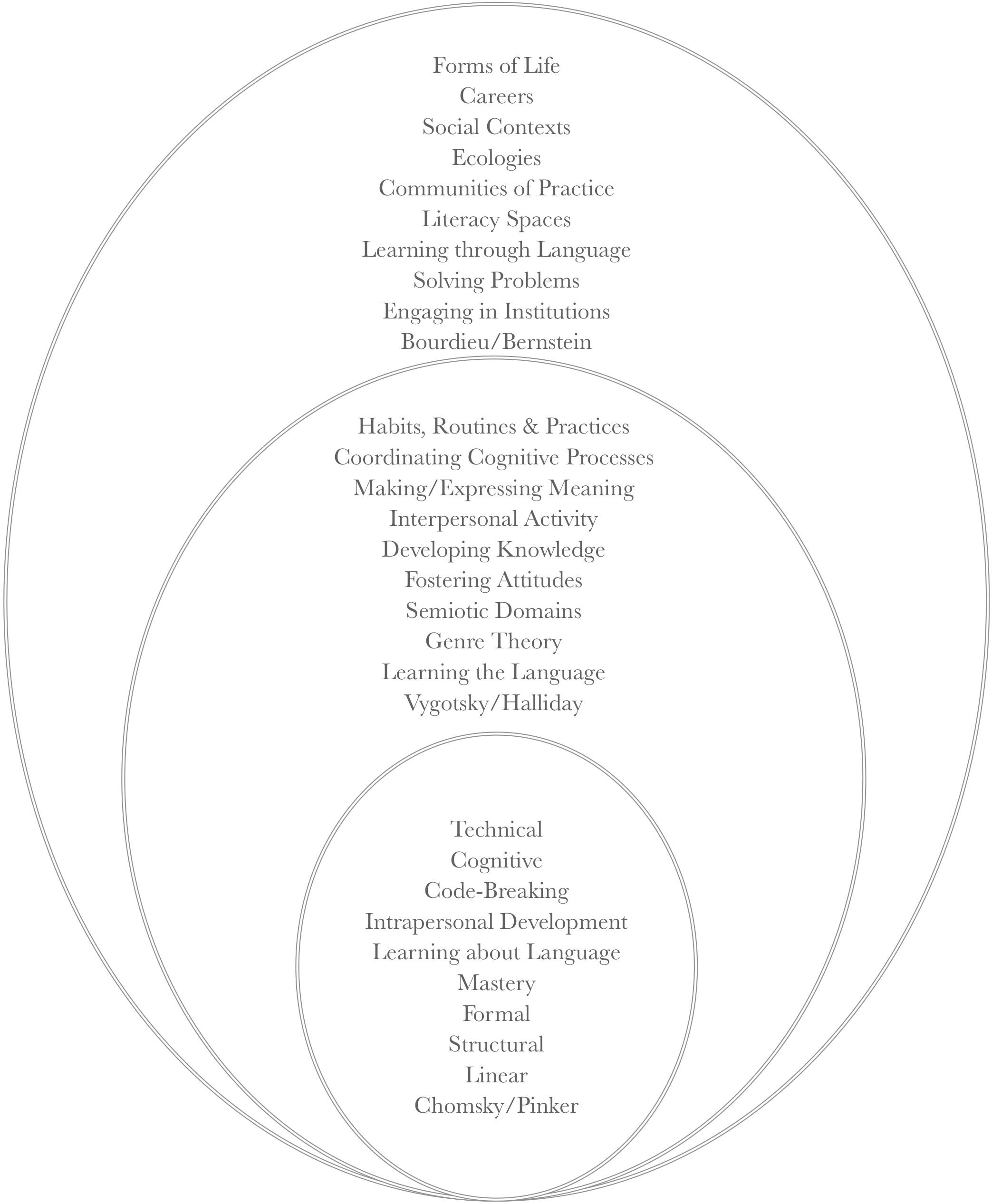

The following "diagram" tries to broach the dichotomy once again. On the left hand side, there are the formal elements of language and literacy. On the right hand side, there are the functional areas to which language and literacy are put to use. And down the centre are quotes which move from a focus on mastery to a focus on application.

Consequently, language and literacy are much more than the mastery of a technique, even though mastery is a significant component of early literacy. The philosopher Rush Rhees (2006) grapples with this temptation to see language as a set of self-contained skills:

"The people who argued with Socrates and Plato may have thought language was just a collection of techniques, and that that was what understanding is: knowing the technique ... For them, the growth of understanding could only mean the growth of skill (efficiency, I suppose) or the multiplication of skills ... A skill would have the sort of unity that a calculus does ... Is understanding just competence?" (pg. 3)

By ending with a rhetorical question, Rhees is expressing some doubt in the idea that understanding is simply a measure of technical proficiency alone. Learning how to spell can be considered to be a technical skill. Knowing how to parse a sentence is also a technical exercise. Yet understanding and communicating are much more complex than technical prowess,

"If you understand anything in language, you must understand what the dialogue is, and you must see how understanding grows as the dialogue grows ... For language is discourse, is speaking. It is telling people things and trying to follow them. And that is what you try to understand ... You understand when it adds to your understanding of the discussion. Or of what the discussion is about." (Rhees, 2006, pg. 7)

At the same time that one is mastering elements of language and literacy, one must be granted opportunities to put these elements into practice, such as through interactive writing, scaffolded discussion, dialogic reading, poetry clubs, anchored instruction, literature circles, the language experience approach and more. In doing so, life is breathed into what would otherwise be cold and lifeless. Whilst it may be convenient to see literacy as a set of skills that are built progressively and mechanically, we must remind ourselves (as Stanley Cavell reminds us),

“The pupil must want to go on alone in taking language [and literacy] to the world, and that what is said must be worth [saying and writing], have a point (warning, informing, amusing, promising, questioning, chastising, counting, insisting, beseeching, specifying the location of pain, and so on) .. If it is part of teaching to undertake to validate these measures of interest, then it would be quite as if teaching must, as it were, undertake to show a reason for [communicating] at all.” (Cavell, 2005, pg 115)

Garver (1996) suggests that the shifting of attention between matters of form and matters of function is no simple act. They represent quite different paradigms.

“If Wittgenstein and Saussure agree in using ‘grammar’ descriptively, they disagree about ... other matters. One is that Wittgenstein’s grammar has to do with uses of language (discourse conditions and discourse continuation) rather than forms and their combinations (morphology and syntax) ...

"Considering uses rather than forms is a deep rather than a superficial departure from classical linguistic methodology ... Studying uses of language makes context prominent, whereas the study of forms lends itself naturally to analysis.” (Garver, 1996, pg 151)

Formal theories of meaning seek to explain how a language expresses a sense through an understanding of the language's logical structure. One must have access to the phonetic, syntactic and lexical knowledge to be able to decode sentences and to decipher the pictures expressed by them. This process is an analytical exchange. In a purely formal account of meaning, the individual would only be required to calculate the exact, unambiguous meaning of a proposition from available signs as long as the proposition was logically expressed and all terms were accounted for clearly and directly.

Meaning-in-context, on the other hand, is less static and more elusive. The meaning of an utterance requires an understanding of its context, a familiarity with the way the utterance is being exchanged, the intention of the utterance, and the position of the utterance within a 'language game' or 'conversation'. Such a theory of meaning must take into account that the subject is a creative, imaginative agent who extends (or projects) new language practices from prior encounters, and that such meaning is framed by the individual's social and discourse practices. Becoming literate also requires that one incorporates the role of “textuality” into one’s life, such as writing lists, emails, letters, notes, poems, etc. And it is bolstered when one experiences positive encounters of meaning making (and learning) with others (e.g. sharing a favourite book with someone you respect).

If I am able to allude to a final theorist here, this dynamic exchange of meaning-making is what Bakhtin (1981) refers to as the dialogic imagination. And it is the dialogic imagination that propels the text (or the logic of a text) forward. In other words, it is an explicit or implicit awareness of the underlying dialogue and associations - made up of questions, expectations, motifs, and conventions - that provide the rationale for the shape and significance of a text. Even as a text struggles to be unique, it exists within the frame of prior conversations and experiences. The more familiar one is with certain activities and conversations - or the text's semiotic domain/context - the deeper one will engage with and comprehend the text (Gee, 2003). If this is done in language that is accessible to the learner, then the possibilities for deep learning are extended even further. In this case, the lower order skills of word/sentence recognition are processed more deeply within the higher order skills of verbal reasoning, prior knowledge and extra-rationale interpretation.

What - then - is the point of this long-winded musing? In one sense, it is the continuation of a long-running discussion of the importance of balancing code-based and meaning-based practice. Those who are familiar with this site will see how this discussion features regularly. On another hand, I would like to return to the statement quoted in the title "the pupil must want to go on alone in taking language to the world." In other words, effective teaching builds skills AND provides rich, motivating opportunities to use these skills in committed acts of communication. This adds something even more elusive to the mix: as teachers, we must inspire learners to read, write, speak, listen, learn and express.

References

Bakhtin, M. (1981). The Dialogic Imagination. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Cavell, S. (2005). Philosophy the day after tomorrow. In Philosophy the day after tomorrow (pp. 111 – 131). Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

Garver, N. (1996). Philosophy as grammar. In H. Sluga & D. Stern (Eds.), The Cambridge companion to Wittgenstein (pp. 139 – 170). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gee, J. P. (2003). Opportunity to learn: a language-based perspective on assessment. In Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice, Vol 10, No. 1, pp 27 - 46

Monk, R. (1999, July 29). Wittgenstein’s Forgotten Lesson. Prospect Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/magazine/ray-monk-wittgenstein/#.Uo_n_pHqvGY

Rhees, R. (2006). Wittgenstein and the possibility of discourse (2nd ed.). Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing.