Informed, Targeted Teaching Relies on Quality Assessment Practices

“The only way for us to guard our assertions against distortions - or avoid vacuity in our assertions, is to have a clear view in our reflections of what the ideal is, namely an object of comparison - a yardstick, as it were.”

Introduction

Assessment is an essential part of teaching and learning. It comes in many forms. There are informal and formal methods. Assessments occur before, during and at the end of teaching and learning. Assessment should be a natural element of any educator's practice. It makes sense to ascertain interests, skills, relevance and progress before we teach, as we are teaching, and after the teaching is done. The information garnered from assessments guide educators in selecting content and activities and it helps teachers determine what skills to teach and how to teach them.

That said, we live in an era of high-stakes testing, which can leave a bad taste in the mouth, so to speak. Such tests do not necessarily provide teachers and learners with data in a timely manner that can be used immediately to improve and target teaching. Nor do these tests elicit information that is specific enough to directly impact what teachers need to focus on in the present and upcoming units. Often, these tests dictate what is taught (in a narrow sense) rather then inform quality teaching.

Ideally, we want schools and teachers to include a variety of assessment methods in their practice:

- Diagnostic Assessments, which provide information on the skills and knowledge that learners presently exhibit;

- Screening Assessment, which examine skill areas in greater detail;

- Progress Monitoring, which seek to monitoring goals determined through initial diagnostic and screening tools;

- Formative Assessments, which also help to monitor a learner’s progress toward identified goals/milestones and - therefore - inform how teaching should adapt and evolve;

- Summative or Performance Assessments, which help us determine to what extent learners have mastered or developed their learning;

- Reflective Assessments, which help all parties (teachers and students) reflect on how the learning is progressing; and

- Resource/Environmental Assessments, which help us determine whether we have all the materials that we need to carry out the learning.

We shouldn’t see these forms of assessment as rigid, though. They should be part of the fluid landscape of a teacher’s relationship with his or students, colleagues, classroom, school, community and subject matter. Having a conversation with a learner about their interests can be a form of a diagnostic assessment. Keeping a portfolio of a leaner’s writing can be a way of tracking formative assessment. Providing “in-time feedback” as a learner is performing a task (e.g. solving a math problem or reading out loud) is a form of assessment, practice and correction. And arranging a discussion with learners to talk reflectively about topics, about the teaching and about the significance of the learning is a way of assessing both teaching and learning.

Teachers should be driven to observe and collect information around questions in each of the following areas:

- Before: what do I know about this learner (e.g. skills, knowledge, interests, etc), so I can best target my teaching and set quality goals? what are the learner’s strengths? what are weaknesses?

- During: how are the learners going? how do I know they are learning? how do I know if they are on track? what should the learners be achieving at this stage? do I need to provide extra support? or do I need to extend their learning?

- Near the End: how do I know that a learner has consolidated this stage of learning? what does the learner need to demonstrate? Are we ready to move on?

- Throughout: am I covering everything that needs to be covered? is my teaching comprehensive? are there any gaps? do I need extra support?

- Throughout: what has been made available for learners? are we using resources wisely? is there anything further that needs to be made available? have I chosen the right topic? the right reading and writing material?

When teachers are equipped with quality information, they are better able to target their teaching. This is the topic of the podcast to the right/above, which I encourage readers to listen to. The podcast is from the Australian Council for Educational Research, and it interviews Dr. Pete Goss from the Grattan Institute. The following is a link to a report - drafted by Dr Goss and his colleagues - that is referred to in the podcast. Building assessment into individual practices and into school practices is a habit, and a good habit to have. The components of this good habit are as follows:

- Setting goals, which requires the gathering of information and determining next steps;

- Formulating expectations, which requires one to confirm what progress a learner needs to be making at key stages;

- Implementing extra support and extension when we develop the profile of different learners;

- Allowing the learner’s needs & interests to shape the teaching, which require teachers to be thoughtful in their practice;

- Targeting teaching, which is teaching that adapts and evolves as new data is gathered or made available;

- Reflecting on practice, so one is choosing the activities and materials that will have the greatest impact; and

- Continually improving and adjusting practices, which allows teachers to be more confident and knowledgable.

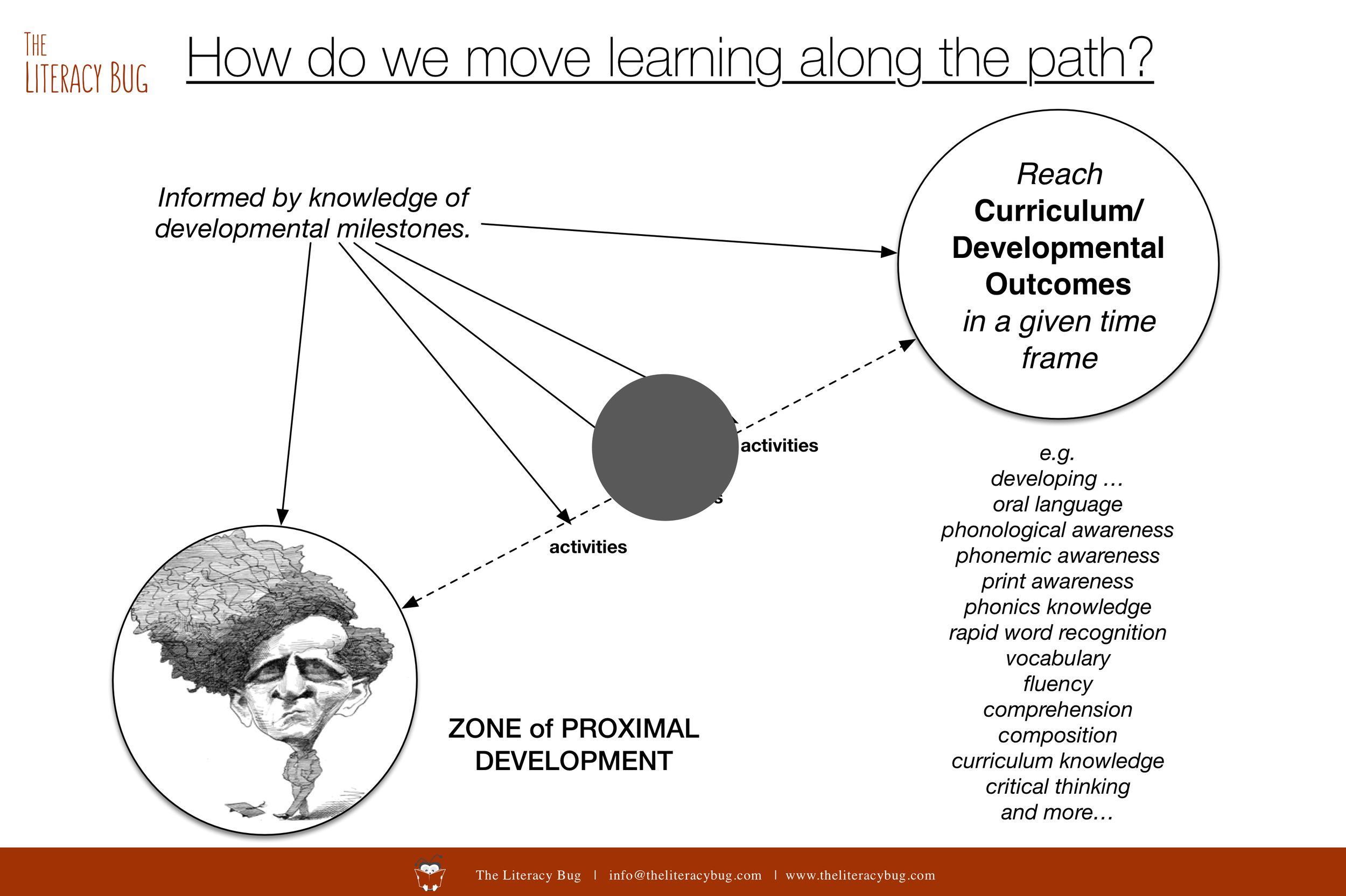

In other words, the goal is informed teaching. In this scenario, teachers and schools develop pictures of successful learners, draw up plans, coordinate delivery, monitor progress and revise teaching as new assessments/observations are made. This is exemplified in the Staircase Curriculum (or Standards Based Change) Model promoted by Kathryn Au and Taffy Raphael. Relevant readings by Au and Raphael can be found at the Whole School Reading List here and through the SchoolRiseUSA website. These perspectives are also very consistent with four of the previous sections on this website: Balancing Instruction, Stages of Development, Establishing Practices, and Developing Constrained Skills.

Strong assessment practices do require professional expertise and decision-making within schools and they often require the support of specialists outside of schools. They require diligence, thoughtfulness, collaboration and creativity. When these practices are not in place, teaching and learning can often become fragmented, inefficient and lack direction. Kids get left behind, and disadvantages becomes exacerbated over time. If we set clear, challenging goals based on strong information, then we can scaffold the many steps required to march toward our learning goals in a timely manner. Along the way, it is often the case that learners surprise us, transform us and exceed our expectations.

'

Assessment As It Specifically Applies to Literacy

In relation to literacy, there a number of areas that teachers need to monitor. These include:

- Cognitive development

- Oral language development

- Developing concepts of print

- Developing phonological and phonemic awareness

- Developing knowledge of letters and letter/sound correspondence

- Developing spelling skills (phonics, orthography and morphology)

- Developing decoding and fluency skills

- Developing comprehension abilities

- Developing (written) compositional skills

- Developing interests, habits and a healthy self-concept as a reader and writer

- Developing knowledge, strategic skills and critical thinking

- Reviewing environmental/contextual factors.

Some of these skills are mastered early on in a learner’s journey, such as concepts of print and phonological awareness, and others are developed throughout a learner’s lifespan, such as oral language skills, writing skills, knowledge and comprehension. This dichotomy is known as the constrained skills theory (Paris, 2005). Constrained skill theory states that literacy development involves the development of two types of skills: constrained skills and unconstrained skills.

Constrained skills includes things like print awareness, phonemic awareness, alphabetic knowledge, spelling, and fluency. These skills are also referred to as print-based or decoding skills, even though phonemic awareness is a pre-print or, rather, language processing skill. The aim of instruction is to achieve ‘mastery’ of these skills (in a relatively short time frame), so that learners can engage deeply and fluidly in intentional, imaginative reading and writing practices. Constrained skills are necessary, though not sufficient, for full literacy. They are best taught and assessed systematically as part of comprehensive language and literacy program.

Unconstrained skills refer to growth in meaning-based skills such as oral language, vocabulary, comprehension, writing/composition, critical thinking skills and general knowledge. These skills are developed across one’s lifetime and become more complex in adolescence and into (young) adulthood. In fact, it has been found that oral language skills are a better indicator of later progress in reading comprehension than word reading (decoding) skills. Word reading (decoding) skills influence reading achievement up to Second Grade; whereas one’s sophistication in oral language ability has a greater bearing on reading (comprehension) ability from Fourth Grade and onward. When one controls for decoding skills (i.e. select individuals who have all developed decoding skills to an adequate level), then unconstrained skills, such as oral language skills, size of vocabulary and depth of background knowledge, all influence one’s ability to comprehend a text. For one to develops these skills, one requires meaningful routines and opportunities to practice in authentic circumstances across all years of schooling.

As a result, assessments must seeks to understand a learner’s development in both constrained and unconstrained skills, even if constrained skills are easier to test (Paris, 2010). The diagram to the right seeks to represent this relationship schematically (select the image to expand). The left side of the “A” includes the elements contributing to oral language comprehension (unconstrained skills); whereas the right side the of the “A” includes the components that lead to robust decoding skills (constrained skills). The second diagram (below) provides constrained and unconstrained skills along a spectrum. The third diagram (also below) provides a visual timeline of the development of literacy-related areas. In this final diagram, one should notice that constrained skills must optimally be mastered in the earlier years of education (e.g. by 9 - 10 years old) to make way for more demanding reading and writing activities from late primary school and into high school and beyond. The fourth and final image (sourced from McKenna & Stahl, 2015), represents constrained skill theory across three levels: constrained skills, such as phonemic awareness, decoding, and fluency practice; vocabulary knowledge, background knowledge and knowledge of text structures; and strategic knowledge (e.g. how to read/write in different ways for different purposes).

Spectrum of Constrained and Unconstrained Literacy Skills

Visual Map of Literacy-Related Developmental Milestones

Cognitive Model adapted from McKenna & Stahl (2009)

Approaches to Assessment

Approaching assessment can be fraught with challenges. When we choose a particular approach, we need to be conscious of the implications of our practice. For instance, there is a growing and - at times - healthy desire to use clear, targeted assessments that monitor the underlying skills which will manifest themselves in full, robust literacy practice. This is an approach adopted by McKenna and Stahl’s Assessment for Reading Instruction (3rd edition). For instance, an individual might begin by ticking off constrained skills that were mentioned in the previous section. Starting with concepts of print, the teacher might use Clay’s An Observation Survey of Early literacy Achievement to map print awareness. Then, the individual might progress through simple phonemic awareness, phonics, decoding, spelling and fluency tests. For reading, the individual might turn to the Qualitative Reading Inventory. In short, the individual is gaining a clear picture of the learner’s potential for reading based on insights gained through the foundational components of reading.

In Understanding and Using Reading Assessment: K-12 (2nd Edition), Afflerbach takes a different approach and one that is more familiar to teachers. In this text, Afflerbach places a greater emphasis on how a teacher judges what a learner demonstrates in authentic literacy tasks. Afflerbach speaks about portfolios, performance measures, reading inventories and the teacher’s targeted questions. If we read between the lines, Afflerbach is prompting teachers to base their judgements upon a student’s corpus of work, his/her interactions in the classroom and his/her responses to carefully selected instructional questions. Whilst McKenna and Stahl’s approach might be clearer, less ambiguous and more linear, Afflerbach’s approach focuses on actual, contextualised literacy practices that children engage in. One approach should not exist to the exclusion of the other, though. And both approaches turn our attention to assessing affective skills like motivation, interests and self-concept, which all have a profound bearing on reading performance.

The summary of the two approaches provides only a rough outline of their perspectives on the topic, and I encourage readers to explore both books in greater depth if they have the chance. Both approaches attempt to view assessment within the realistic contexts of schools. They recognise the time constraints that teachers are under and they acknowledge how testings is gradually encroaching on valuable teaching time. That said, if we are to prepare learners for the present and the future, we need to teach effectively, comprehensively, creatively and strategically.

The following provides an index of assessments which have been categorised by the skills that they assess. Please explore and enjoy!

Example Assessment Tools Organised in Key Areas

Assessment schedules should include a mixture of methods, such as "benchmarking tools" (like the ones listed below), teacher-generated assessments and routine observations (including portfolios). The following are a sample of assessment tools in main areas of teaching and learning. Some of the assessment are quite involved and require specialist to administers; whereas, others are easier to administer, score and interpret.

Assessing cognitive skills

- Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence - 3rd Edition (WPPSI-III)

- Woodcock-Johnson Test of Cognitive Abilities - 3rd Edition (WJ-III)

- Stanford-Binet, 5th Edition (SB-V)

Assessing oral language (pragmatics)

- MacArthur Communicative Development Inventory (CDI)

- Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals - 4th Edition (CELF-4)

- EAL/D Language Learners Progression

Assessing oral language (grammar)

- Progressive Achievement Tests in Written Spelling, Punctuation and Grammar (PAT-SPG)

- Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals - 4th Edition (CELF-4)

Assessing oral language (vocabulary)

- Peabody Picture Vocabulary Task IV

- Expressive Vocabulary Test (2nd Edition)

- Vocabulary Knowledge Scale

Assessing early literacy skills (concepts of print)

- An Observation Survey of Early Literacy Achievement

- Test of Preschool Early Literacy

- Letter Sound Short Form Assessment

Assessing phonological & phonemic awareness

- School Entry Alphabetic & Phonological Awareness Readiness Test (SEAPART)

- Test of Phonological Awareness (TOPA)

Assessing spelling development (phonics, spelling & morphology)

- Z-Test

- Informal Phonics Inventory

- South Australian Spelling Test

- Qualitative Spelling Inventory

Assessing decoding & fluency

- Informal Decoding Inventory

- Qualitative Reading Inventory (Word Lists & Graded Passages)

- Running Records

- 4 x 4 Oral Reading Assessment

Assessing quality of read aloud

- Picture Walk Scoring Guidelines

- Read Aloud Rating Effectiveness Form (Observation or Videotaped Reflection)

- Systematic Assessment of Book Reading (SABR)

Assessing reading comprehension

- Qualitative Reading Inventory (Word Lists & Graded Passages)

- Gray MacGinite Reading Tests

- Tests of Reading Comprehension (TORCH) 3rd Edition

- Purposes of Reading Interview

Assessing writing & composition

- NSW Literacy Continuum

- EAL/D Language Learners Progression

- Progressive Achievement Tests in Written Spelling, Punctuation and Grammar (PAT-SPG)

- Teacher Generated Rubrics

Assessing attitudes interests & motivation

- Elementary Reading Attitudes Survey

- Motivation to Read Profile - Revised Survey of Adolescent Reading Attitudes

- Reading Self-Concept Scale

Assessing environments & resources

- Morrow’s Checklist of Effective Classroom Environments

- Early Childhood Environmental Scale:

- The Child/Home Environmental Language and Literacy Observation

- Classroom Literacy Environmental Profile (CLEP)

Assessing quality of instruction

- Whole School Literacy Review - (UK National Literacy Trust)

- Staircase Curriculum Model - Standards-Based Change model from SchoolRiseUSA

- Principal Walkthrough Checklists - K-12 (Florida Centre for Reading Research)

Using developmental continua

- NSW Literacy Continuum

- The Continuum of Literacy Learning (K-8): Behaviours and Understandings to Notice, Teach and Support.

- New Zealand Literacy Learning Progressions

- ESL Scales

- EAL/D Language Learners Progression

Conclusion

Assessments should inform teaching and the content that we select to teach. Too often, assessment is seen as something that occurs only at the end of a unit. However, if we gather important baseline data, then we can teach in a much more informed manner. We can target skills and avoid unnecessary instruction. This information does not lead to a smooth road, though. A teacher is required to be ever-vigilant in making everyday decisions and in orchestrating a range of scaffolded activities. Teachers need to be organised, creative, caring and insightful. The more we know about our students and how they are progressing, the better equipped we will be in helping them on their respective journeys in becoming imaginative, critical and effective readers and writers.

General Assessment Readings

Afflerbach, P. (2012) Understanding and using reading assessment: K-12 (2nd Ed). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). (2014). English as an Additional Language or Dialect Teacher Resource EAL/D Learning Progression: Foundation to Year 10. Sydney.

Curriculum Corporation. (1997). ESL Scales. Melbourne: Curriculum Press.

Dickinson, D. K., McCabe, A., & Sprague, K. (2001). Teacher Rating of Oral Language and Literacy (TROLL): A Research-Based Tool. CIERA Report #3-016. Ann Arbor, MI.

Fountas, I. C., & Pinnell, G. S. (2007). The Continuum of Literacy Learning (K-8): Behaviours and Understandings to Notice, Teach and Support. Portsmouth: Heinemann.

Gove, A., & Wetterberg, A. (Eds.). (2011). The Early Grade Reading Assessment: Applications and Interventions. Raleigh, NC: Research Triangle Institute.

Hoffman, J. V., Sailors, M., Duffy, G. R., & Beretvas, S. N. (2004). The effective elementary classroom literacy environment: Examining the validity of the TEX-IN3 observation system. Journal of Literacy Research, 36(3), 303-334.

International Reading Association (2013). Formative assessment: a position statement of the International Reading Association. Newark, DE: IRA.

Justice, L. M. (2006). Evidence-based practice, response to intervention, and the prevention of reading difficulties. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 37(4), 284-297.

Justice, L. M., Mashburn, A., Hamre, B., & Pianta, R. (2008). Quality of Language and Literacy Instruction in Preschool Classrooms Serving At-Risk Pupils. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23(1), 51–68. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2007.09.004

Lesaux, N. K., & Marietta, S. H. (2011). Making assessment matter: Using test results to differentiate reading instruction. New York: Guilford Press.

Leslie, L. & Caldwell, J. S. (2010). Qualitative Reading Inventory (5th edition). Boston: Pearson.

McKenna, M. (2001). Development of reading attitudes. In L. Verhoeven & C. Snow (Eds.), Literacy and motivation: reading engagement in individuals and groups (pp. 135–158). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Mckenna, M. C., Conradi, K., & Meyer, J. P. (2012). Reading Attitudes of Middle School Students: Results of a U. S. Survey. Reading Research Quarterly, 47(3), 283–306. doi:10.1002/RRQ.021

McKenna, M. C., & Stahl, K. A. D. (2009). Assessment for reading instruction (ebook) (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

McKenna, M. C., & Stahl, K. A. D. (2015). Assessment for reading instruction (ebook) (3rd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Morsy, L., Kieffer, M., & Snow, C. (2010). Measure for Measure: A Critical Consumers’ Guide to Reading Comprehension Assessments for Adolescents. Final Report from Carnegie Corporation of New York’s Council on Advancing Adolescent Literacy. Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Moss, P., Pullin, D., Gee, J. P., Haertel, E., & Young, L (Eds.) (2008), Assessment, equity, and opportunity to learn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

National Child Care Information Center (2004). Early language and literacy observation and assessment tools. Vienna, VA: National Child Care Information Center.

New Zealand Ministry of Education. (2010). The Literacy Learning Progressions: Meeting the Reading and Writing Demands of the Curriculum. Wellington: Learning Media Limited.

NSW Department of Education and Communities. (2011). NSW Literacy Continuum. NSW Department of Education and Training. Retrieved July 26, 2014, from http://www.curriculumsupport.education.nsw.gov.au/literacy/

Nilsson, N. L. (2008), A Critical Analysis of Eight Informal Reading Inventories. The Reading Teacher, 61: 526–536. dos: 10.1598/RT.61.7.2

Paris, S. G. (2010). Problems with Early Reading Tests: Confounded Statistical Analyses and Policy Recommendations. In 36th Annual Conference of the International Association of Educational Assessment. Retrieved from http://www.iaea.info/documents/paper_4d2285cb.pdf

Shanahan, C. (2005). Adolescent Literacy Intervention Programs: Chart and Program Review Guide. Naperville, IL.

Shepard, L. A. (2005). Linking Formative Assessment to Scaffolding. Educational leadership, 63(3), 66-70.

Spear-Swerling, L., & Cheesman, E. (2012). Teachers’ knowledge base for implementing response-to-intervention models in reading. Reading and Writing, 25(7), 1691–1723. doi:10.1007/s11145-011-9338-3

Paris, S. G. (2005). Reinterpreting the development of reading skills. Reading Research Quarterly, 40(2), 184–202. doi:10.1598/RRQ.40.2.3

Paris, S. G. (2010). Problems with Early Reading Tests: Confounded Statistical Analyses and Policy Recommendations. In 36th Annual Conference of the International Association of Educational Assessment. Retrieved from http://www.iaea.info/documents/paper_4d2285cb.pdf

Swanson, E., & Vaughan, S. (2011). Implementing a response to intervention model to improve reading outcomes for all students. In What research has to say about reading instruction (4th ed., pp. 266 – 285). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Westberg, L., McShane, S., & Smith, L. (2006). Verizon Life Span Literacy Matrix: Relevant Outcomes, Measures and Research-based Practices and Strategies. Washington D.C.

Assessing Literacy Environments

Chiu, M. M., McBride-Chang, C., & Lin, D. (2012). Ecological, psychological, and cognitive components of reading difficulties: testing the component model of reading in fourth graders across 38 countries. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 45(5), 391–405. doi:10.1177/0022219411431241

Clay, M. M. (2013). An observation survey of early literacy achievement (3rd edition). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann

Davidse, N. J., de Jong, M. T., Bus, A. G., Huijbregts, S. C. J., & Swaab, H. (2011). Cognitive and environmental predictors of early literacy skills. Reading and Writing, 24(4), 395–412. doi:10.1007/s11145-010-9233-3

Grinder, E. L. (2007). Review of early childhood classroom observation measures. Harrisburg, PA: Pennsylvania’s Departments of Education and Public Welfare.

Harms, T., Clifford, R. M., & Cryer, D. (2005). Early Childhood Environmental Rating Scale: Revised edition. New York: Teachers College Press.

Hoffman, J., Sailors, M., Duffy, G., & Beretvas, S. N. (2004). The effective elementary classroom literacy environment: examining the validity of the TEX-IN3 observation system. Journal of Literacy Research, 36(3), 303–334. doi:10.1207/s15548430jlr3603_3

Landry, S. H., Crawford, A., Gunnewig, S., & Swank, P. R. (2002). Teacher Behavior Rating Scale. Unpublished research instrument. Centre for Improving Readiness of Children for Learning and Education, University of Texas Health Science Centre at Houston

Morrow, L. M. (1990). Preparing the classroom environment to promote literacy during play. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 5, 537-554.

Morrow, L. M. (2002). The literacy centre: Contexts for reading and writing (2nd ed.). Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

National Child Care Information Center (2004). Early language and literacy observation and assessment tools. Vienna, VA: National Child Care Information Center.

Neuman, S. B., Koh, S., & Dwyer, J. (2008). CHELLO: The Child/Home Environmental Language and Literacy Observation. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23(2), 159–172. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2007.11.001

Pinnell, G. S., & Fountas, I. C. (2011). Literacy Beginnings: A Prekindergarten Handbook. Portsmouth: Heinemann.

Reutzel, D. R., & Wolfersberger, M. E. (1996). An environmental impact statement: Designing supportive literacy classrooms for young children. Reading Horizons, 36, 266-282.

Senechal, M. (2006). Testing the Home Literacy Model: Parent Involvement in Kindergarten Is Differentially Related to Grade 4 Reading Comprehension, Fluency, Spelling, and Reading for Pleasure. Scientific Studies of Reading, 10(1), 59–87. doi:10.1207/s1532799xssr1001_4

Smith, M. W., & Dickinson, D. K. (2002). Early Literacy and Language Classroom Observation—Research edition. Baltimore: Brookes.

Smith, M. W., Dickinson, D. K., & Sangeorge, A. (2008). The early language and literacy classroom observation 2 (Rev. ed.). Baltimore: Brookes Publishing.

Taylor, B. M., & Pearson, P. D. (2000). The CIERA School Change Classroom Observation Scheme. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota.

Wilcox, M. J., Gray, S. I., Guimond, A. B., & Lafferty, A. E. (2011). Efficacy of the TELL language and literacy curriculum for preschoolers with developmental speech and/or language impairment. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 26(3), 278–294. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2010.12.003

Wolfersberger, M., Reutzel, D. R., Sudweeks, R., & Fawson, P. (2004). Developing and validating the Classroom Literacy Environmental Profile (CLEP): a tool for examining the “print richness” of early childhood and elementary classrooms. Journal of Literacy Research, 36(2), 211–272. doi:10.1207/s15548430jlr3602_4

Managing Whole School Literacy Practices

Allington, R. L. (2007). Intervention All Day Long: New Hope for Struggling Readers. Voices from the Middle, 14(4), 7–14.

Au, K. H.-P. (2005). Negotiating the Slippery Slope : School Change and Literacy Achievement. Journal of Literacy Research, 37(3), 267–286.

Au, K. H.-P. (2006). Schoolwide change to improve literacy achievement. In Multicultural issues and literacy achievement (pp. 173–194). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Au, K. H.-P. (2010). Real schools, real success: a roadmap for change. Reading Forum New Zealand, 25(1), 25–35.

Au, K. H.-P. (2013). Helping high schools meet higher standards. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 56(7), 535–539.

Au, K. H.-P., & Raphael, T. E. (2011). The staircase curriculum: whole-school collaboration to improve literacy achievement. New England Reading Association Journal, 46(2), 1–8.

Au, K. H.-P., Raphael, T. E., & Mooney, K. C. (2008). Improving Reading Achievement in Elementary School: Guiding Change in a Time of Standards. In S. B. Wepner & D. S. Strickland (Eds.), Supervision of Reading Programs (4th ed., pp. 71–89). New York: Teachers College Press.

Au, K. H.-P., Strode, E. V., Vasquez, J. M., & Raphael, T. E. (2014). Improving literacy achievement in elementary schools: the standards-based change process and the common core. In S. B. Wepner, D. S. Strickland, & D. J. Quatroche (Eds.), The Administration and Supervision of Reading Programs (pp. 74–83). New York: Teachers College Press.

Denton, C., Bryan, D., Wexler, J., Reed, D., & Vaughn, S. (2007). Effective Instruction for Middle School Students with Reading Difficulties: The Reading Teacher’s Sourcebook. Dallas, TX.

Fisher, D., & Frey, N. (2007). Implementing a Schoolwide Literacy Framework: Improving Achievement in an Urban Elementary School. The Reading Teacher, 61(1), 32–43. doi:10.1598/RT.61.1.4

Grant, P. A., South Australian Primary Principals Association, & Dept of Education and Children’s Services. (2003). Nothing left to chance: Report on literacy and numeracy outcomes evaluation in high achieving disadvantaged schools. Adelaide.

Hawkins, M. R. (2004). Researching English Language and Literacy Development in Schools. Educational Researcher, 33(3), 14–25. doi:10.3102/0013189X033003014

Irvin, J., Meltzer, J., & Dukes, M. S. (2007). Develop and Implement a Schoolwide Literacy Action Plan. In Taking Action on Adolescent Literacy. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Jensen, B., Farmer, J., Hunter, J., & Cooper, S. (2014). Turning around schools: it can be done. Carlton, VIC.

Justice, L. M. (2006). Evidence-based practice, response to intervention, and the prevention of reading difficulties. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 37(4), 284–297. doi:10.1044/0161-1461(2006/033)

Lawrence, J. F., Capotosto, L., Branum-Martin, L., White, C., & Snow, C. E. (2012). Language proficiency, home-language status, and English vocabulary development: A longitudinal follow-up of the Word Generation program. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 15(03), 437–451. doi:10.1017/s1366728911000393

Lawrence, J., Rolland, R. G., Branum-Martin, L., & Snow, C. E. (2014). Generating Vocabulary Knowledge for At- Risk Middle School Readers: Contrasting Program Effects and Growth Trajectories. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk (JESPAR), 19(2), 37–41.

Lesaux, N. K., & Marietta, S. H. (2011). Making assessment matter: Using test results to differentiate reading instruction. New York: Guilford Press.

Martin, M., Fergus, E., & Noguera, P. (2010). Responding to the needs of the whole child: a case study of a high-performing elementary school for immigrant children. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 26(3), 195–222. doi:10.1080/10573561003769582

May, S. (2007). Sustaining Effective Literacy Practices Over Time in Secondary Schools: School Organisational and Change Issues. Language and Education, 21(5), 387–405. doi:10.2167/le799.0

McKenna, M. C., & Stahl, K. A. D. (2009). Assessment for reading instruction (ebook) (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Mosenthal, J., Lipson, M., Mekkelsen, J., & Thomspon, E. (2003). The Dynamic Environment of Success: Representing School Improvement in Literacy Learning and Instruction. In Paper presented at the National Reading Conference.

Newmann, F. M., Smith, B., Allensworth, E., & Bryk, A. S. (2001). Instructional Program Coherence: What It Is and Why It Should Guide School Improvement Policy. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 23(4), 297–321. doi:10.3102/01623737023004297

Raphael, T. E., Au, K. H., & Goldman, S. R. (2009). Whole school instructional improvement through the standards-based change process. In J. Hoffman & Y. Goodman (Eds.), Changing Literacies for Changing Times (pp. 198–229). New York: Routledge/Taylor Frances Group.

Raphael, T. E., Au, K. H., & Popp, J. S. (2013). Transformative practices for literacy teaching and learning : a complicated agenda for literacy researchers. In S. Szabo, L. Martin, T. Morrison, L. Haas, & L. Garza-Garcia (Eds.), Literacy is transformative: 35th annual yearbook of the association of literacy educators and researchers (pp. 9–32). Louisville, KY: Association of Literacy Educators and Researchers.

Raphael, T. E., Weber, C., Goldman, S., Sullivan, M. P., & George, M. (2005). Defying gravity: literacy reform in urban schools. Journal of Literacy Research, 37(3), 267–286.

Spear-Swerling, L., & Cheesman, E. (2012). Teachers’ knowledge base for implementing response-to-intervention models in reading. Reading and Writing, 25(7), 1691–1723. doi:10.1007/s11145-011-9338-3

Strategic Educational Research Partnership. (2009). Word generation. Retrieved from http://www.wordgeneration.org

Swanson, E., & Vaughan, S. (2011). Implementing a responsive to intervention model to improve reading outcomes for all students. In What research has to say about reading instruction (4th ed., pp. 266 – 285). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Taylor, B. (2007). The what and the how of good classroom reading instruction in the elementary grades. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Center for Reading Research

Taylor, B.M., Pearson, P. D., Clark, K., & Walpole, S. (2000). Effective schools and accomplished teachers: Lessons about primary-grade reading instruction in low-income schools. Elementary School Journal, 101, 121-166.

Tivnan, T. & Hemphill, L. (2005). Comparing four literacy reform models in high-poverty schools: patterns of first-grade achievement. In The Elementary School Journal, 105(5), 419-441

Tunmer, W. E., Chapman, J. W., Greaney, K. T., Prochnow, J. E., & Arrow, A. W. (2013). Why the New Zealand national literacy strategy has failed and what can be done about it: evidence from the progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) 2011 and Reading Recovery Monitoring Reports.

Vaughn, S., Cirino, P. T., Wanzek, J., Wexler, J., Fletcher, J. M., Denton, C. D., … Francis, D. J. (2010). Response to Intervention for Middle School Students With Reading Difficulties: Effects of a Primary and Secondary Intervention. School Psychology Review, 39(1), 3–21. Retrieved from http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3072689&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract

Walpole, S., Justice, L. M., & Invernizzi, M. a. (2004). Closing the Gap Between Research and Practice: Case Study of School-Wide Literacy Reform. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 20(3), 261–283. doi:10.1080/10573560490429078

Weber, C. M., Raphael, T. E., Goldman, S. R., Sullivan, M. P., & George, M. (2009). Literacy coaches: multiple issues, multiple roles, multiple approaches. Elementary School Journal, October.