Part Two: Decoding

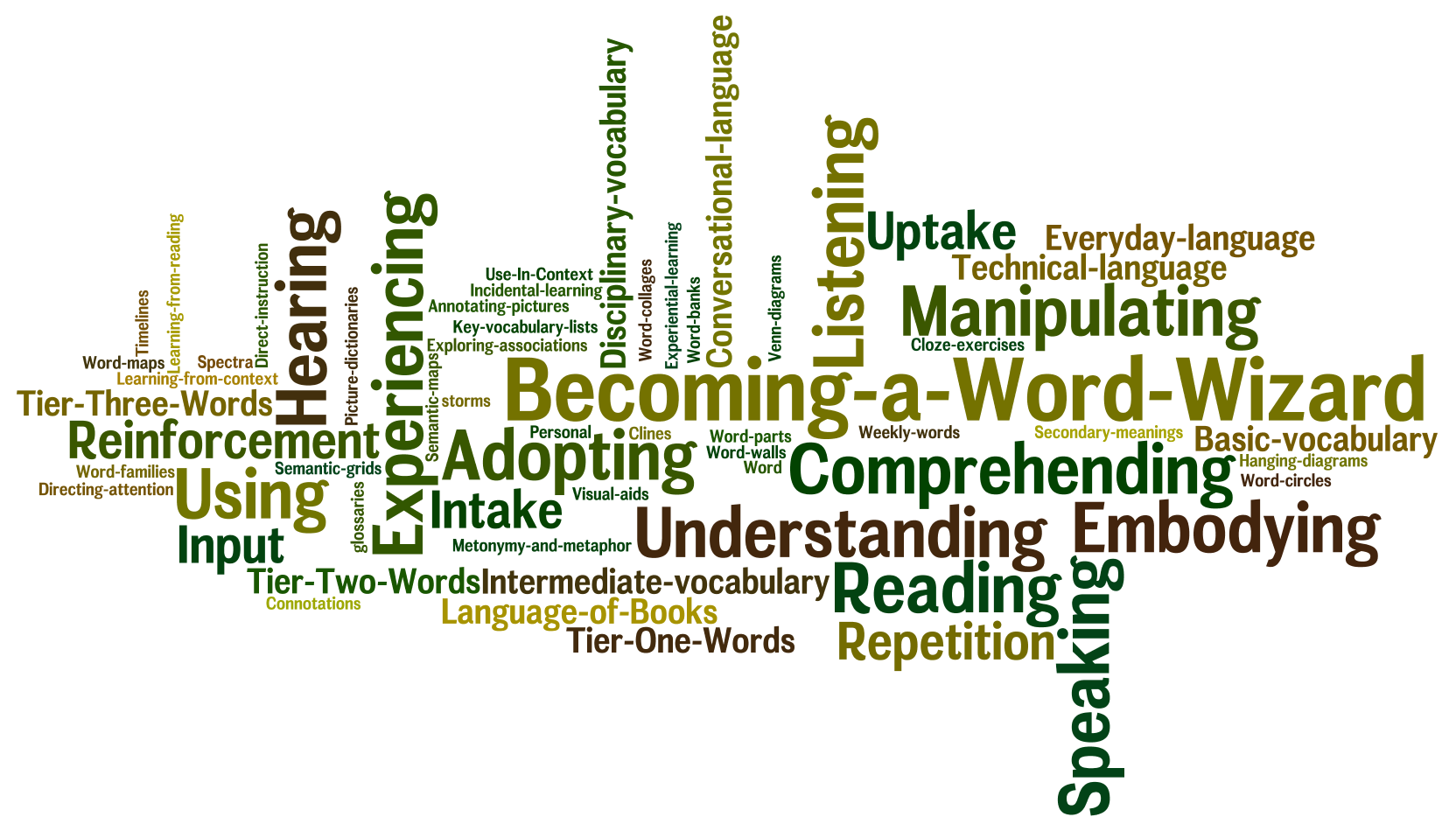

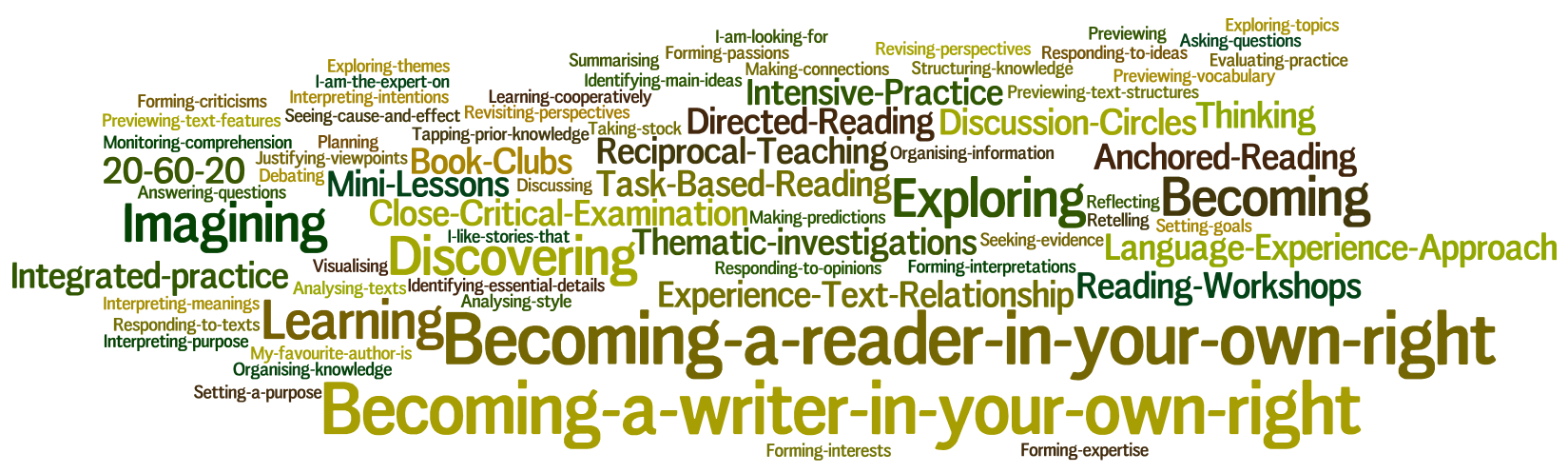

Eventually, the tables are turned, though. It is no longer enough to be able spell words by relying upon the stimulation of internal and external speech. The learner will need to decode words that are presented first in print. The learner will need to derive oral language from print, which will require that he or she recognises regular patterns, such as phonics patterns, syllable constructions, sight words, word families, morphological regularities and more.

By 6 - 7 years of age, a child is experiencing direct instruction in letter-sound relations (phonics) as well as practice in their use. He or she is reading simple stories using words with these phonic elements as well as high frequency words. By ages 7 - 8, direct instruction extends to include advanced decoding skills along with wide reading of familiar, interesting materials that help promote fluency. Meanwhile, the child is being read to at levels above their own independent reading level to develop language, vocabulary and concepts (Chall, 1996). The child should be motivated to extend themselves in relation to both expressiveness and comprehension.

PRINT WORD(S) ---> DIVIDED INTO SYLLABLES & GRAPHEMES ---> SOUNDED OUT ---> RECOGNISED ---> VOICED FLUENTLY [EITHER AUDIBLY OR INAUDIBLY] ---> UNDERSTOOD IN CONTEXT

The sequence when reading words in isolation as well as those in connected text is:

- Do I see the word(s) and attend to the word(s)?

- Do I recognise it/them as one(s) I know? Do I recognise it/them immediately or do I need to decode it/them? Can I begin to guess it/them based on context and other cues? Do I simply recognise it/them or can I also sound it/them out?

- Can I "chunk it/them"? (e.g. identify syllables, onset-rime and graphemes)

- Can I allocate sound(s) to individual letters or letter combinations (e.g. graphemes)?

- Can I refine how the word or words are read in syllables and use my knowledge of patterns to read more proficiently and meaningfully?

- Can I recognise the word or words along with words around it/them (if applicable)?

- Can I re-read the word or words and the sentence (if applicable) with expression and confidence?

- Do I consider the meaning of the word, the current utterance and other potential utterances?

- Can the learner begin to develop a more systematic understanding of how English words work?

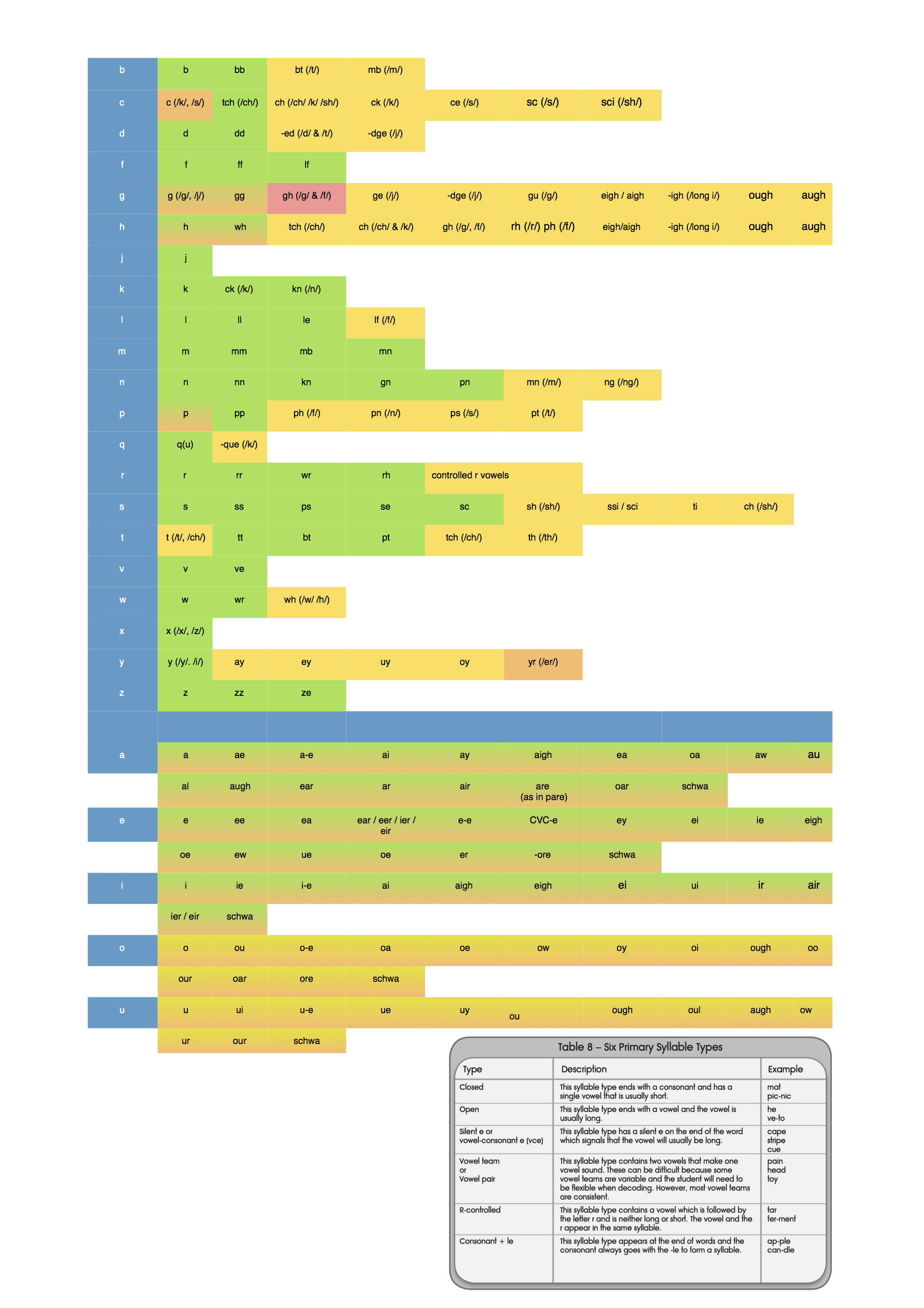

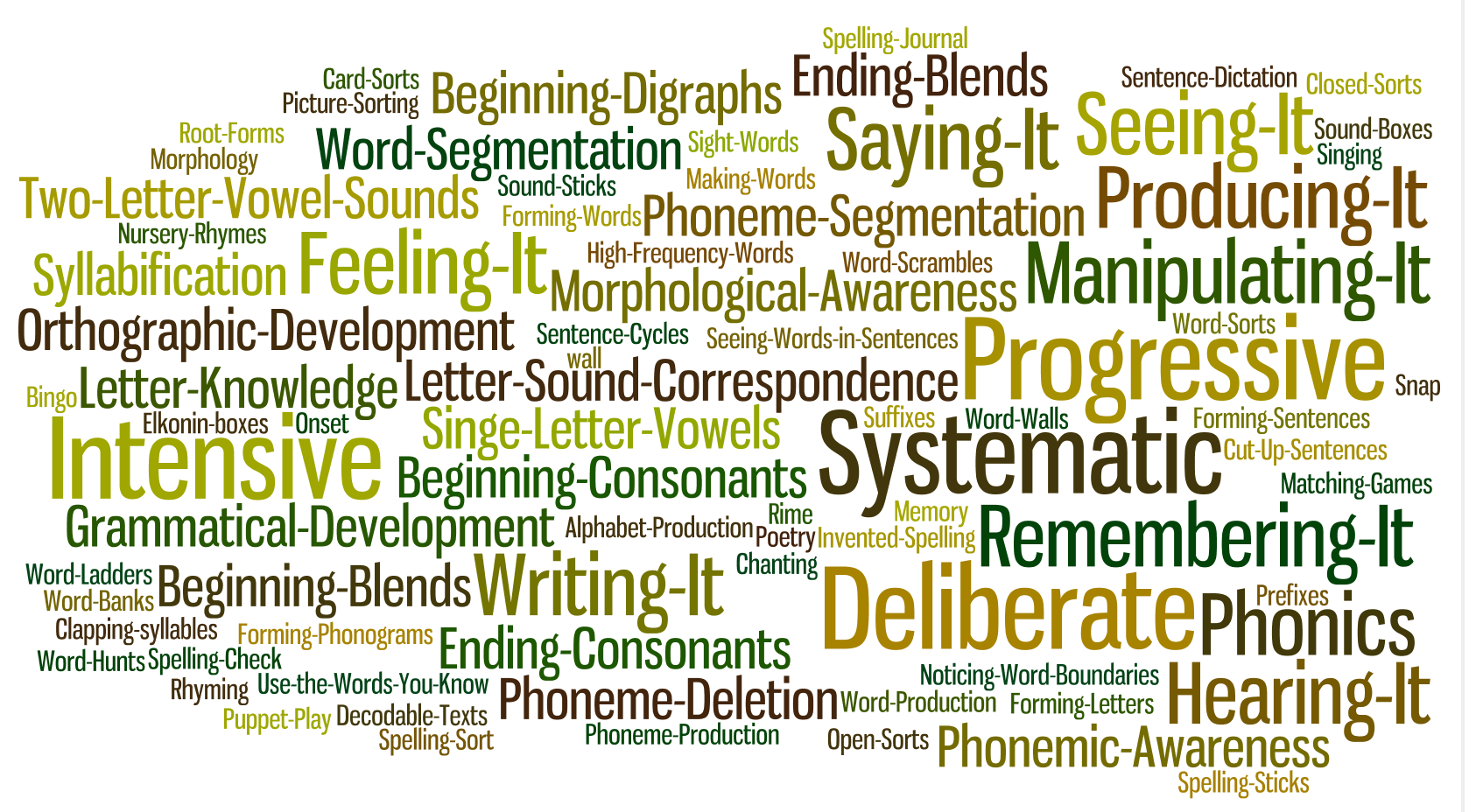

As learners firmly grasp the concepts of words, phonemes, graphemes and morphemes, then it becomes more feasible to systematically study graphemes in what would be called a synthetic manner. This would extend to involve further exercises which refine the learner's knowledge of spelling rules, stress patterns and more. For the moment, consider the following order of phonics to be taught in a synthetic manner (source: Bear, et al., 2015):

Letter Name-Alphabetic (Semi-Phonetic) Stage [typically between 4 - 7 yrs old]: CVC word patterns with the following sequence of graphemes and blends: short a, m, t, s, short i, f, d, r, short o, g, l, h, short u, c, b, n, k, v, short e, w, j, p, y, x, q, z, sh, ch, th, wh, st-, pl-, bl-, gl-, sl-, sp-, cr, cl, fl, fr, sk, qu, nk, ng, mp, ck

Within Word (Transitional) Stage [typically between 7 - 9 yrs old]: CVCe word patterns leading into more complex CVVC vowel patterns and common multisyllabic words: a-e, ai, ay, ei, ey, ee, ea, ie, e-e, i-e, igh, y, o-e, oa, ow, u-e, oo, ew, vowel+r, oi, oy, ou, au, ow, kn, wr, gn, shr, thr, squ, spl, tch, dge, ge, homophones

Syllables & Affixes (Independent) Stage [typically between 9 - 11 yrs old]: multisyllabic words, adding inflectional endings, homographs & homophones

Derivation (Advanced) Stage [typically between 11 - 14 yrs old]: focusing on advanced prefixes, suffixes, roots as well as word families (e.g. exclaim, exclamation, exclamatory)

In this model, learners become familiar with letter-sounds after they are supported to navigate sounds-to-letters. Furthermore, one is exploring language well before this or - at least - alongside this study. Upon recognising words from a string of letters and/or sounds, and pictures/intentions from a string of words, then there is hope that learners can process that which has been portrayed within the coded text as well as in the spoken stream. There is hope that one is informing and being informed; is entertaining and being entertained; is greeting and being greeted; etc.