It is with the greatest of pleasures that we share our latest presentation - Applying Our Understanding to Real-World Case Studies.

This presentation is the culmination of recent work, and it is an important next step in putting one’s growing knowledge of literacy development to use. We may know certain things intellectually - such as the stages of literacy development or the components of literacy - but the true test lies in putting this knowledge into practice.

For the purposes of this presentation, viewers will be asked to reflect upon the needs and circumstances of individual learners, and to use this information as the basis of instructional planning.

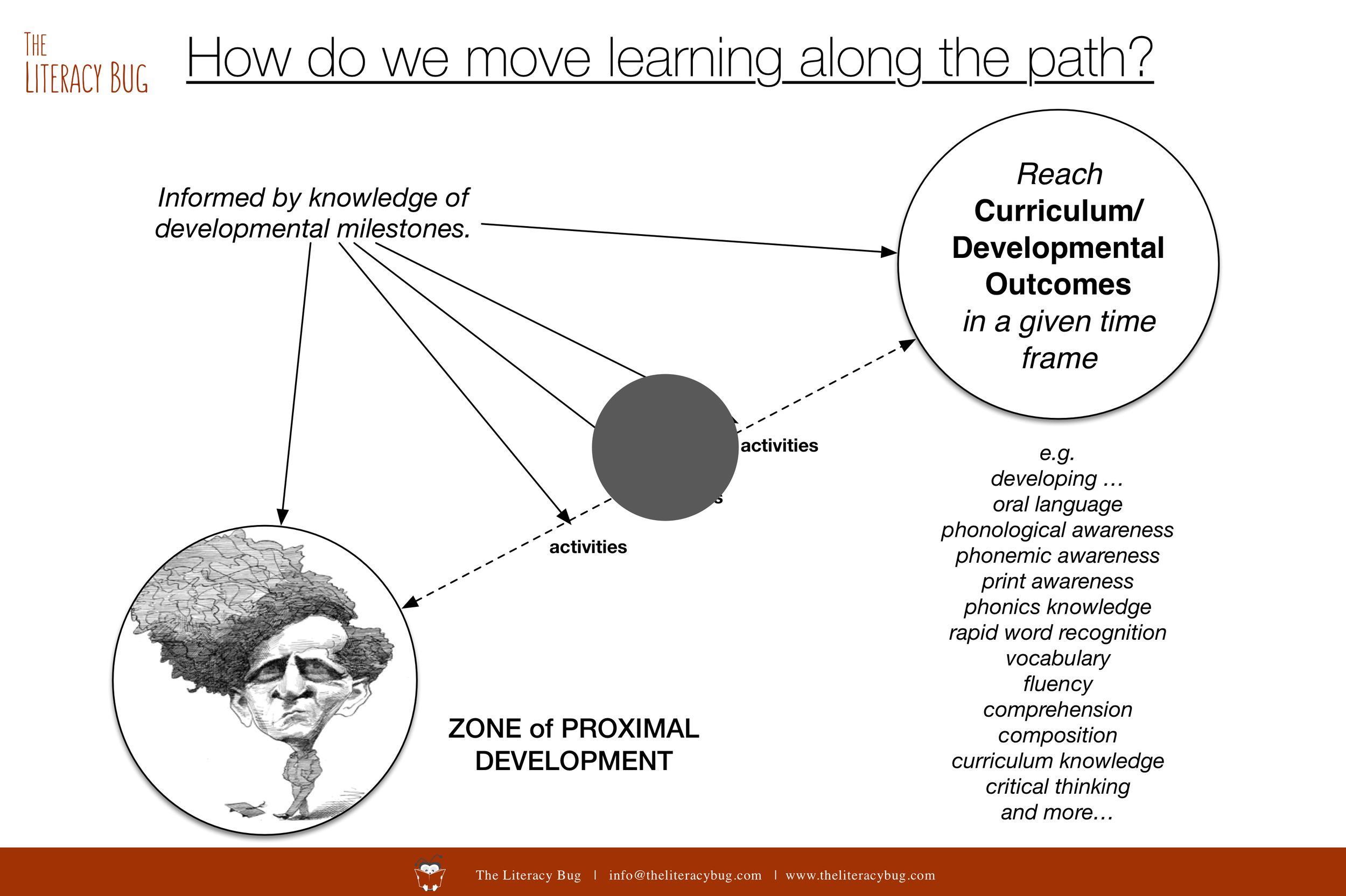

We all know that literacy instruction cannot be a one-size-fits-all solution. For best practice, we need to know where a learner is placed along the literacy journey, so we can provide those experiences that will help the learner continue along in his or her journey.

We must see the enormous potential for profound growth in each learner, and we must commit ourselves to providing learners with the right type and amount of sustained practice to make literacy acquisition a reality.

Ultimately, what is it that we want? We want learners to be able explore, learn and express - fluently and intelligently. We want learners to be able to take control of the script, so they are able use literacy actively and critically for a range of purposes.

Without further ado, we invite you to explore the presentation above. Within the presentation, you will meet Maria, Jonathan, Dakota and David. In the future, we plan to introduce you to a whole cast of others with a focus on providing further opportunities for you to critically reflect and respond to the needs and circumstances of a diverse range of learners.

Please explore the video and download the related slides, which can be found above and on YouTube at https://youtu.be/u7eP9nBFG-U. The presentation slides can be downloaded at http://bit.ly/2-Apply-Case-Studies. We highly recommend that you download the slides, since they contain the case studies as well as suggested activities.

I wish I could be delivering this presentation in a face-to-face seminar to The Literacy Bug audience. I’d be very curious to know the personal perspectives that you’d bring to the content and the case studies. In the abscence of this opportunity, I encourage you to email your ideas to us at ebrace@theliteracybug.com, or leave a comment below or on YouTube. Please explore and enjoy!

To recap, the following are links to the other presentations in the series:

An Overview of Literacy Development

YouTube Video: https://youtu.be/yMGU7UIJ4RU

Slides: http://bit.ly/2-Overview-Literacy-v2

Planning and Monitoring for Effective Instruction

YouTube Video: https://youtu.be/cZrtB8dTZEg

Slides: http://bit.ly/2-Planning-Monitoring-2

Teaching According to the Stages of Development

YouTube Video: https://youtu.be/D7vUhqVXLWg

Slides: http://bit.ly/2-Teaching-Routines-Stages-2

Additional Resources for the Planning and Monitoring for Effective Instruction

YouTube Video: https://youtu.be/R71j5_kegzk

Slides: http://bit.ly/2-Planning-Monitoring-Resources-2

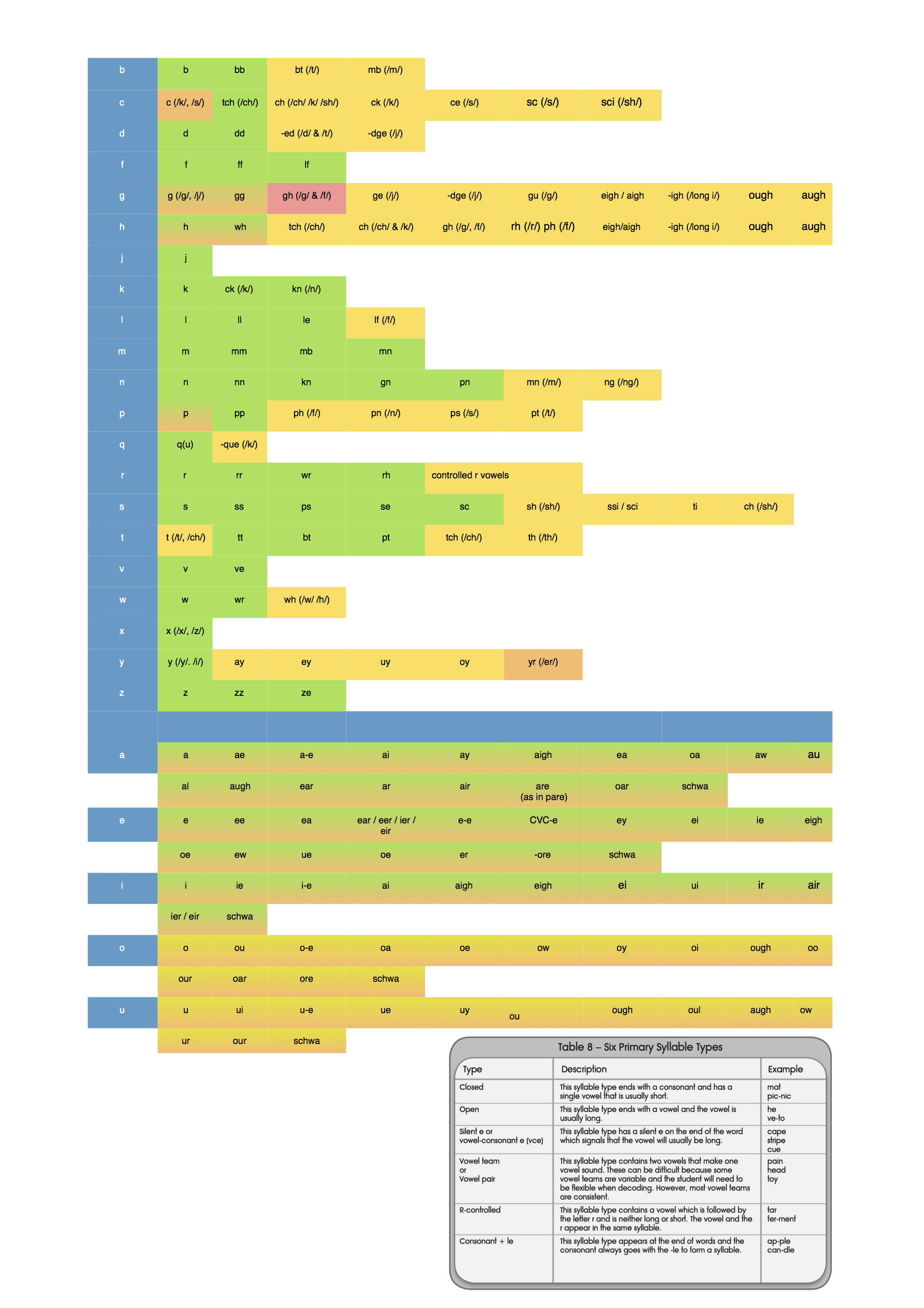

Mastering the Alphabetic Principle

YouTube Video: https://youtu.be/dA4nt3rxTYM

Slides: http://bit.ly/Mastering-the-Code

Analysing Spoken Words

YouTube Video: https://youtu.be/8DVPbK0HSyY

Blog Entry: https://www.theliteracybug.com/journal/2018/9/3/analysing-spoken-words-a-new-activity

Words Sorts

YouTube Video: https://youtu.be/HCvYgHk6ODc

Blog Entry: https://www.theliteracybug.com/journal/2018/9/3/word-sorts

Sentence: Types, Features and Structures

Slides: http://bit.ly/2-The-Sentence