Some may downplay this announcement as merely routine site maintenance. In actual fact, an update to the site's glossaries and reading lists is news that significant progress has been made to the very foundations of the online resource.

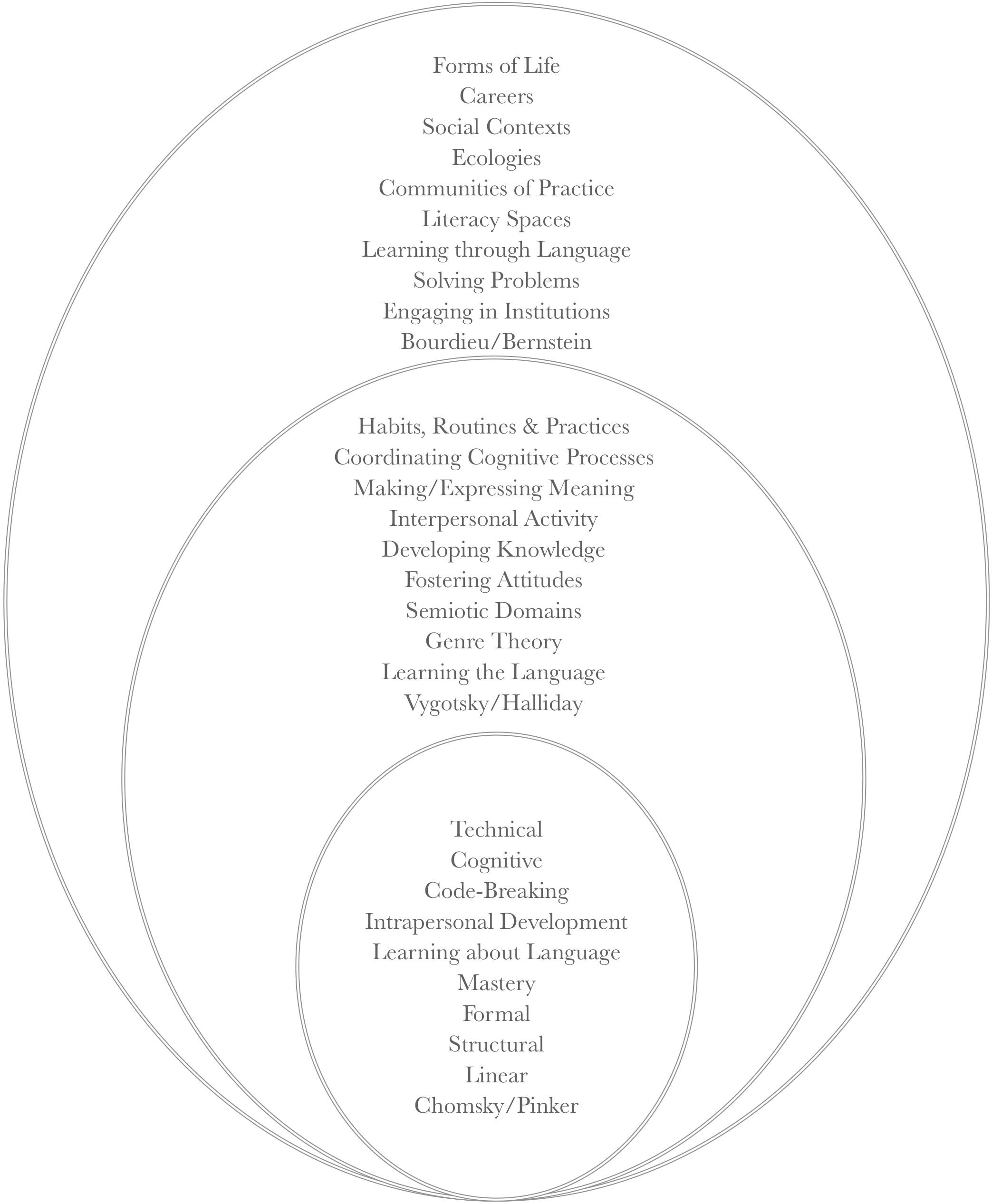

Firstly, progress is finally being made to the Literacy Glossary. This resource is a work-in-progress. A core list of 70 terms/concepts will be part of the initial list. These terms/concepts will be added over the coming weeks. A further announcement will be made once the Literacy Glossary is fully drafted.

Secondly, there is a range of additions that have been made to the Literacy-Related Reading Lists. In the Contexts of Literacy Instruction section, I have added readings related to the Language Experience Approach (LEA). LEA is an pedagogy whereby shared experiences (e.g. gardening, going out bush, cooking, etc) become the basis for interactive writing exercises which - in turn - produce texts that serve as sources of further reading practice. Teachers and students can use digital photography and information scaffolds to document experiences, and this documentation can be used to recreate, recount and extend upon the shared experiences. Teachers are also encourage to focus on particular words for word study and vocabulary exercises. LEA is an effective teaching technique for younger students and beginning English language learners. More about the Language Experience Approach will be written in the near future. In the meantime, please explore the readings.

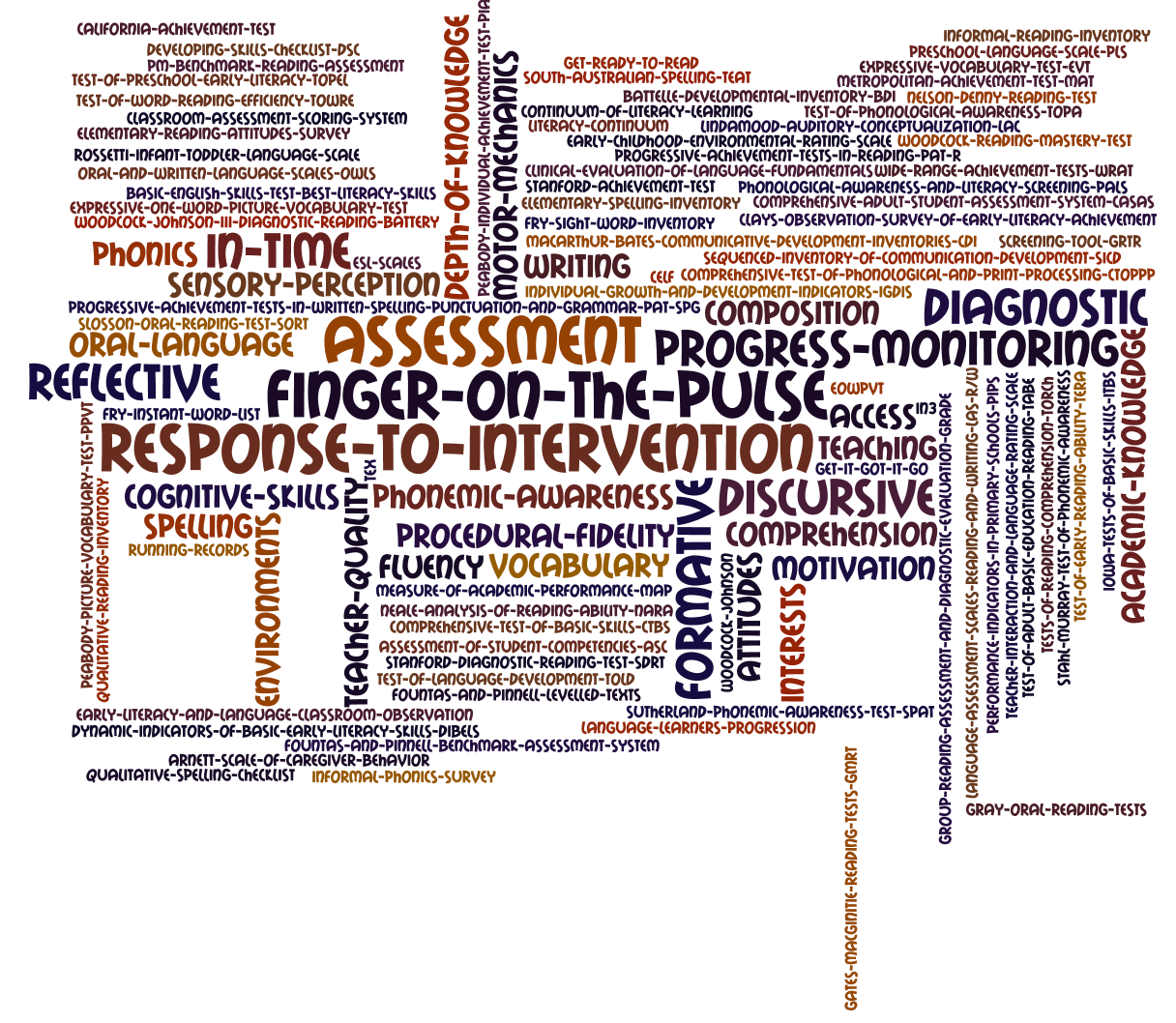

Two reading lists have also been added to the Elements of Instruction section of the readings: Supporting Fluency and Assessment Tools. This rounds out the Elements section. The lists mirror the five pillars of effective reading instruction (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2000), whilst also including an emphasis on writing and oral language development. Effective instruction must foster the development of phonemic awareness, letter-sound correspondence (including spelling), vocabulary, oral language, reading fluency, reading comprehension and writing/composing. The Supporting Fluency reading list provides a brief yet comprehensive list of references, whilst the Assessment Tools reading list will grow over time.

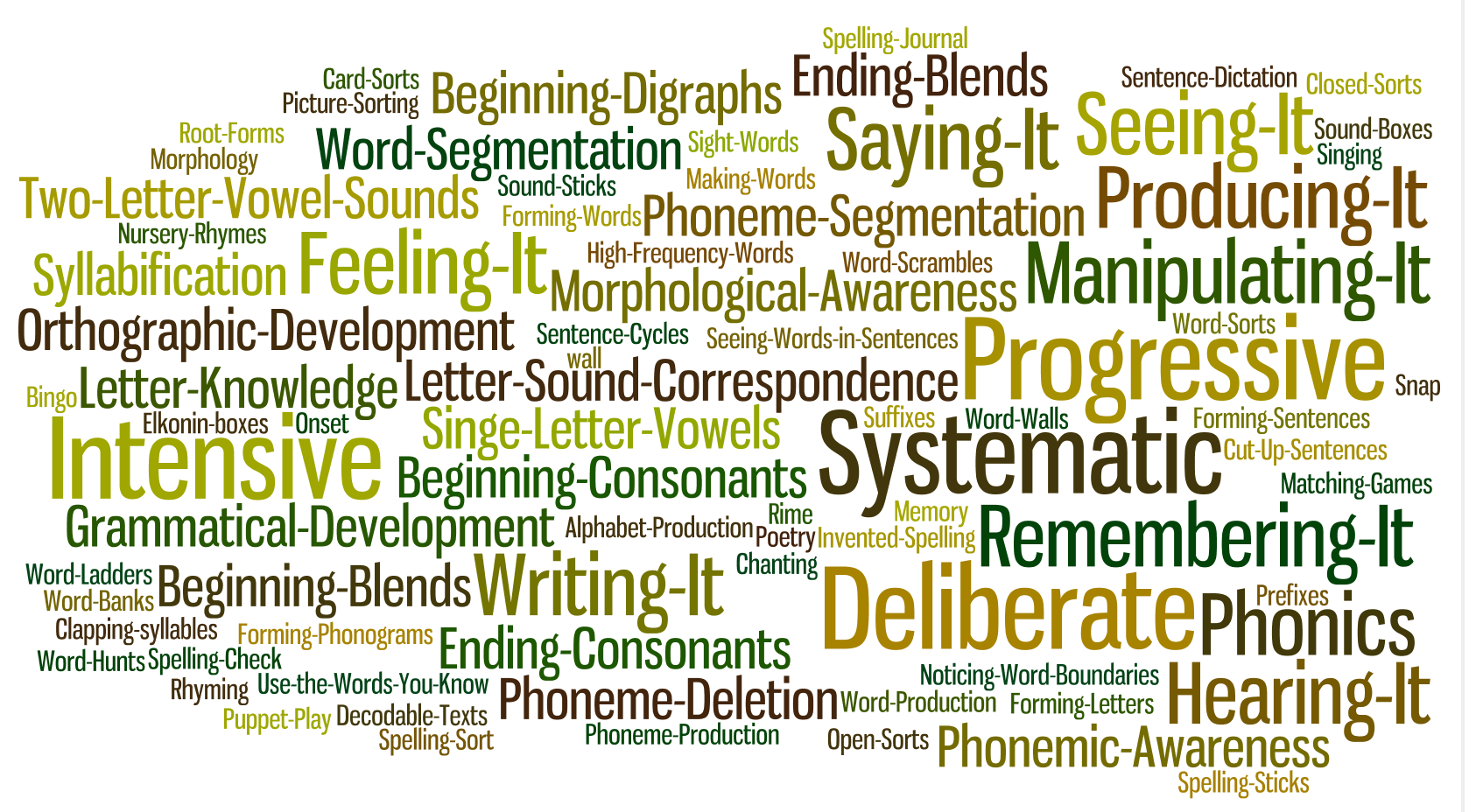

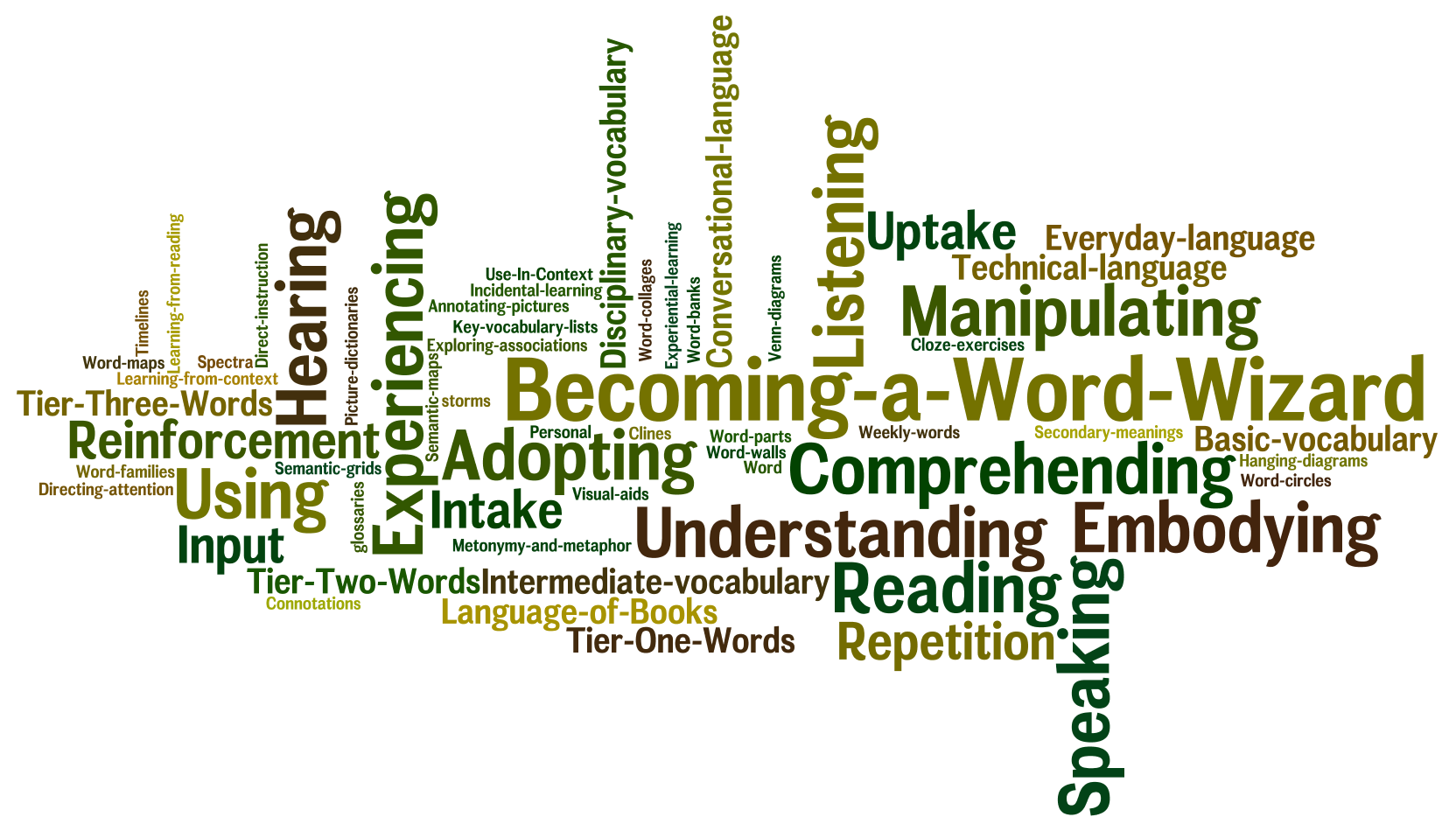

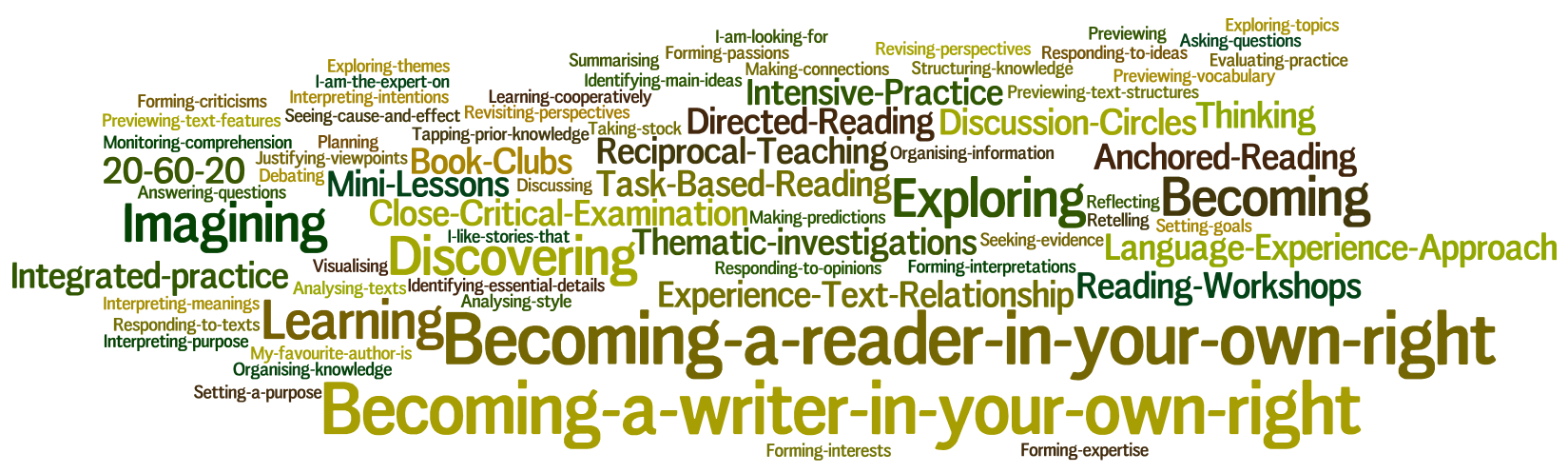

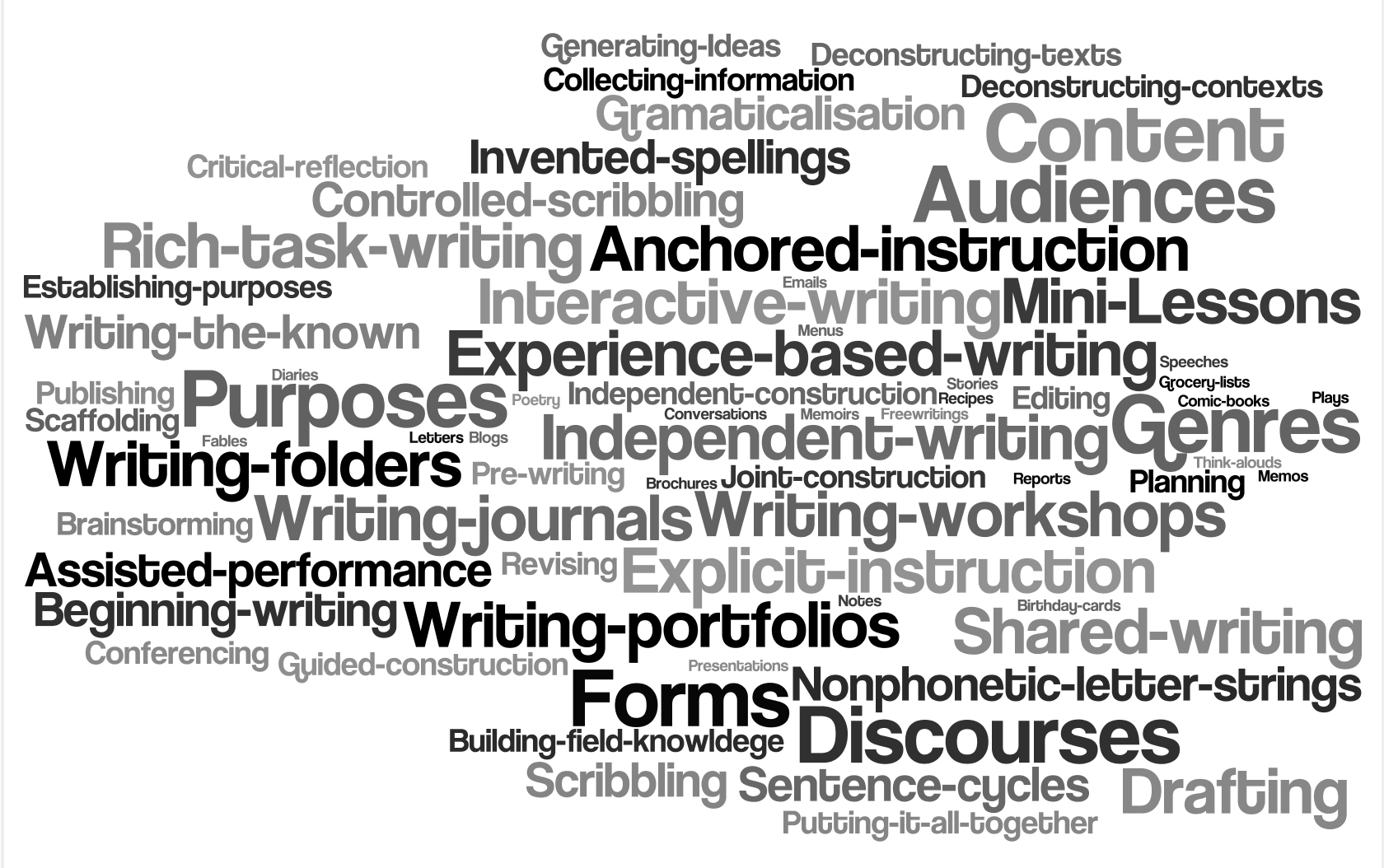

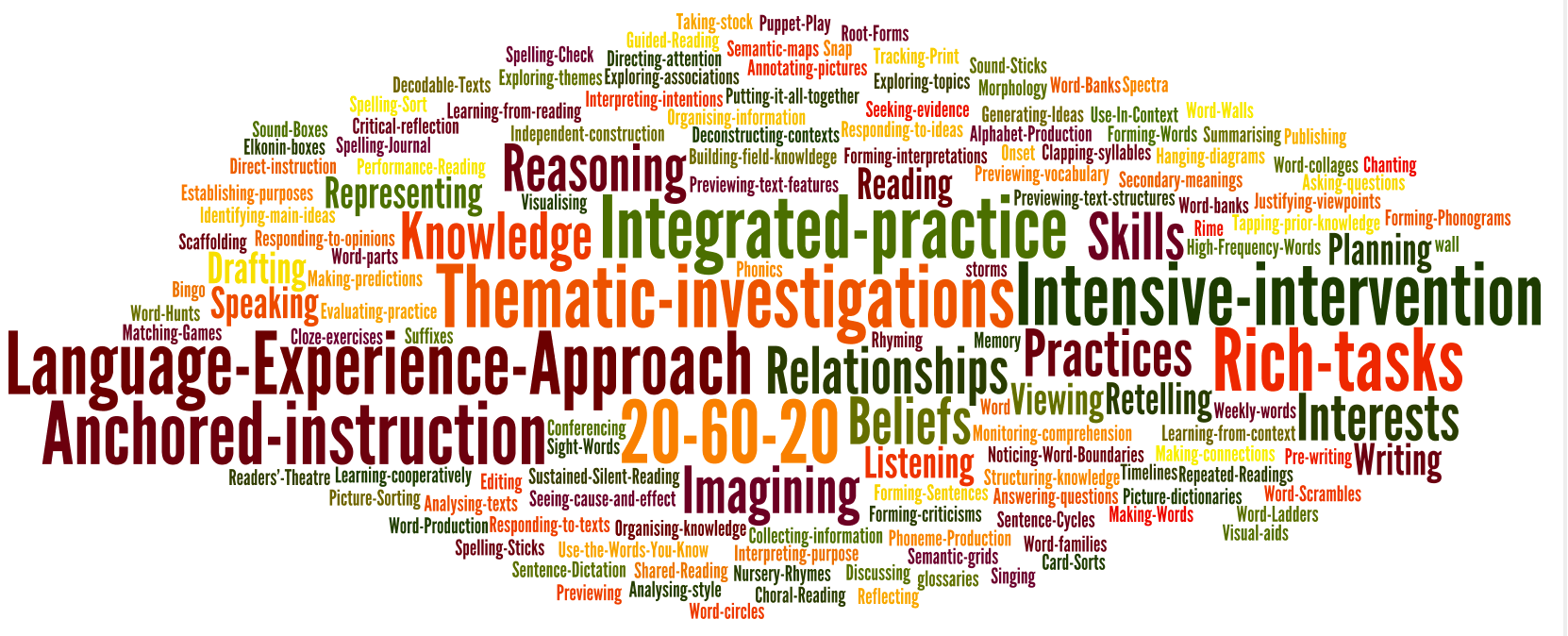

Last but not least, word clouds have been added to each of the reading lists in the Elements of Instruction section. The logic of the word clouds will be revealed in a future resource. In the meantime, the following is a gallery of the collected clouds. Please enjoy and explore!

Reference

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel. Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction (NIH Publication No. 00-4769). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.